Knobbed Whelk Captures Large Quahog

The weather has been “overcast November” heading into “icy December” in the Great White North. While days have been in the low 40s, nights in the mid 20s, winds have been too feeble and too southerly to bring any cold-stunned turtles onto the beach. Those animals that still float about in hypothermic stupor, tossed this way and that by wind and tide, will have to wait until the next strong storm system hits the Cape before they come ashore for rescue. In the mean time, we patrol beaches for the odd turtle that might have stumbled onto shore, and we sweep the wrack line for interesting discoveries. So, forgive us as we take a brief trip backwards in the Turtle Journal “Time Machine” to the warmth of summer, prompted by whelk egg casings we have found recently in Wellfleet Bay.

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

Knobbed Whelk (Busycon carica) in Sippican Harbor

We ran across a mature knobbed whelk (Busycon carica) while kayaking in Sippican Harbor for terrapins during the summer. This animal had hunted down a large quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria) and held it firmly in the grasp of its powerful foot. The whelk was fully engaged in splitting open the bivalve for a delicious dinner. As we examined and documented this snail, it soon became disturbed by our intrusion and dropped its prey to reveal its complete visceral anatomy.

Channeled Whelk (Busycotupus canaliculatus)

The Turtle Journal team has encountered two large whelk species around Cape Cod: knobbed whelks (Busycon carica) and channeled whelks (Busycotupus canaliculatus).  These large (5 to 12 inches) predatory sea snails are considered “right-handed” because when held with the spire up and siphonal canal down, the aperture is on the right (dextral) side. [NOTE: The lightning whelk (Busycon perversum, found in the south and the Gulf of Mexico) as its name implies is sinistral with the aperture on the left side.] Knobbed whelks have tubercles or spines along the shoulder. Channeled whelks are slightly smaller than knobbed whelks and have smooth shells with deep square channels that are continuous on all whorls.

Knobbed Whelk (Busycon carica)

The apperture contains the whelk’s viserca covered by an operculum (horny door) that protects these snails from predators and desiccation. Major identifiable body parts include the foot (closest to the operculum), two chemosensory tentacles, two light sensitive eyes behind the tentacles, a proboscis between the tentacles with a mouth at the end, and a siphon.

Knobbed Whelk Re-Engages with Quahog Prey

Whelks reside in intertidal and subtidal zones along sandy and muddy bottoms. Clam and oyster reefs can be important habitats as these are prey for whelks. These snails migrate from shallow waters in the spring and summer to deeper waters in the winter. They will bury into the sand for protection during storms. A whelk will wedge the edge of its shell between the two shells of a bivalve. Then, when the two shells are forced ajar, the whelk inserts its proboscis and radulla (rasping tongue) into the soft body of the bivalve.

Live Horseshoe Crabs (Left) to Bait Whelk Traps (Right) in Buzzards Bay

The most serious predators are humans who harvest whelks as a commercial fishery even here in Massachusetts. Beyond removing these graceful, giant gastropods from the seascape, the second tragedy of the whelk fishery is the bait of choice that is used to attract whelks into traps: chopped and quartered horseshoe crabs, live or frozen. [Note: We will be posting an article on the whelk fishery after the sea turtle rescue season.] Europeans are heavy consumers of whelk, which is sometimes sold as “conch” and is also marketed as scungilli for Italians.

Chiton

And now for something really different, as Monty Python might say. The critter Don mentioned in the video clip that the Turtle Journal team had encountered in great numbers on the Reefs beach in Southampton, Bermuda is the chiton. The photograph above shows the chiton we found on the knobbed whelk with Sue’s fingernail for size comparison. According to Wikipedia, chitons are primitive marine mollusks with somewhere between 900 and 1000 existing species and are sometimes called sea cradles or coat-of-mail shells.  The chiton shell consists of eight separate imbricated (overlapping) plates.

Channeled Whelk Casings: Some Opened, Some Plugged

Whelk mating occurs in spring and fall. They are thought to be protandric hermaphrodites, which means that they function first as males when young and smaller, and then whelks change to females as they grow larger and age. So, a fishery that targets larger animals, whether through regulation or fancy, will preferentially eliminate productive females from the ecosystem.Â

Females produce egg capsules or casings attached to a “string.” A string might hold 100 to 120 capsules, with each case containing as many as 35 eggs. One end of the string is secured to the bottom of the bay and eggs develop into very tiny whelks within the casings. After hatching, small juvenile snails emerge through a predesigned exit hole (see photograph above). Most egg casings that wash up on the beach, dredged from the bay floor by nature or man, are empty because the tiny juvenile snails have successfully emerged.

Â

Peterson Field Guides “Atlantic Seahshore” – Kenneth L. Gosner

The Peterson Field Guide for Atlantic Seashore offers an excellent diagram of the difference between channeled and knobbed whelk casings. Within our area of the coast, the overwhelming number of casings we find are channeled whelks … such as the one that came from Burton Baker Beach which we will examine in detail below.Â

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

Examining Channeled Whelk Plugged Casing

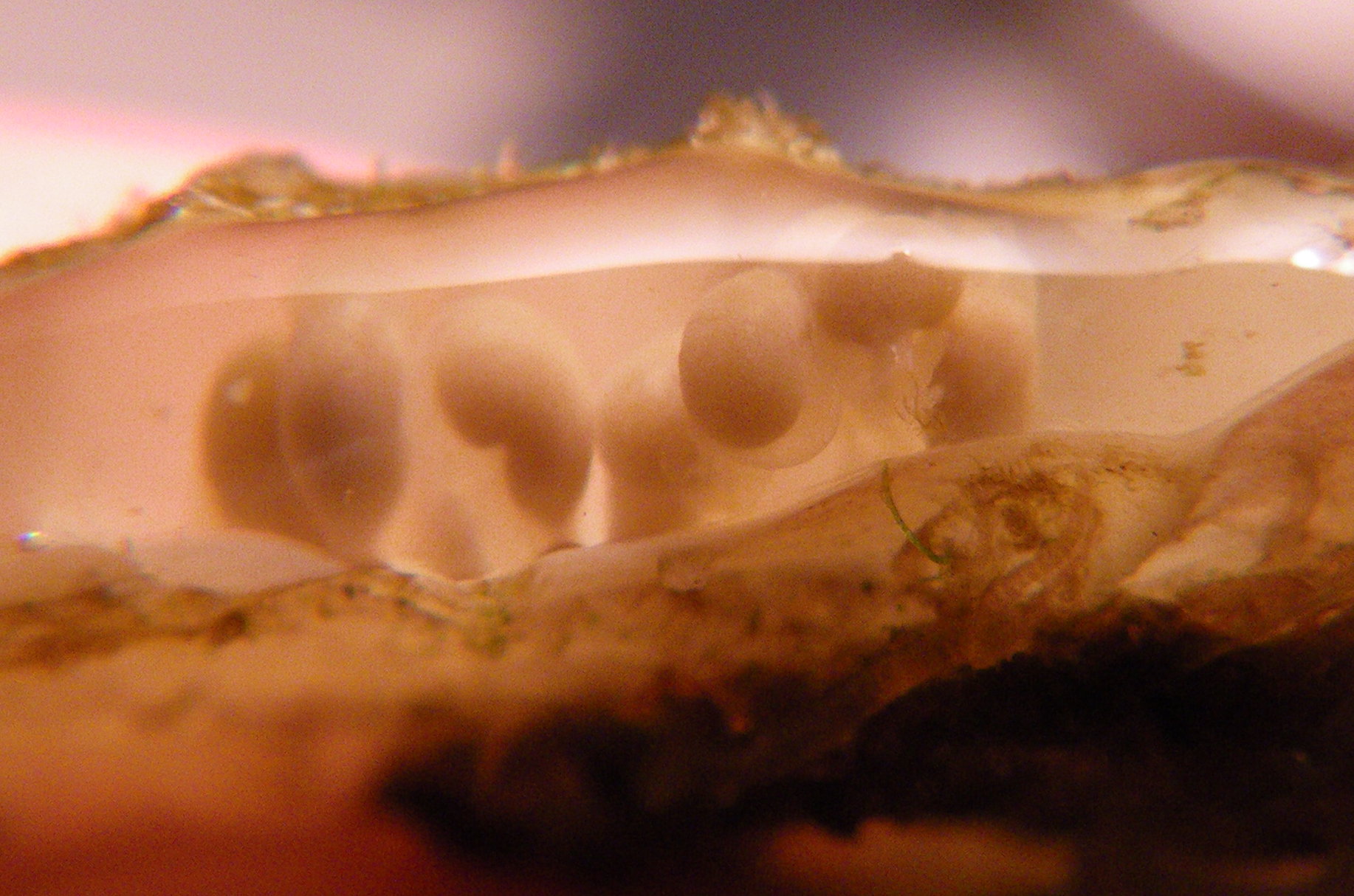

Most casings that we find on Cape beaches have already hatched; many of the capsules have opened and presumably the tiny whelks that had developed from the eggs inside the casings have already emerged. The chain we found at Burton Baker Beach was different. It contained mostly plugged cases and we selected one of these plugged casings that still felt full of fluid for closer examination. With a small scissors we snipped the edge along the plugged emergence hole, revealing tiny developing whelk shells inside.

Tiny Baby Channeled Whelks

Little whelks were still suspended in gooey fluid and seemed to be in the process of developing their exterior shells. Since most of the casings in this string were still plugged and the whelks had not yet begun to emerge, we assessed that the tiny whelks had not yet developed sufficently to survive independently.

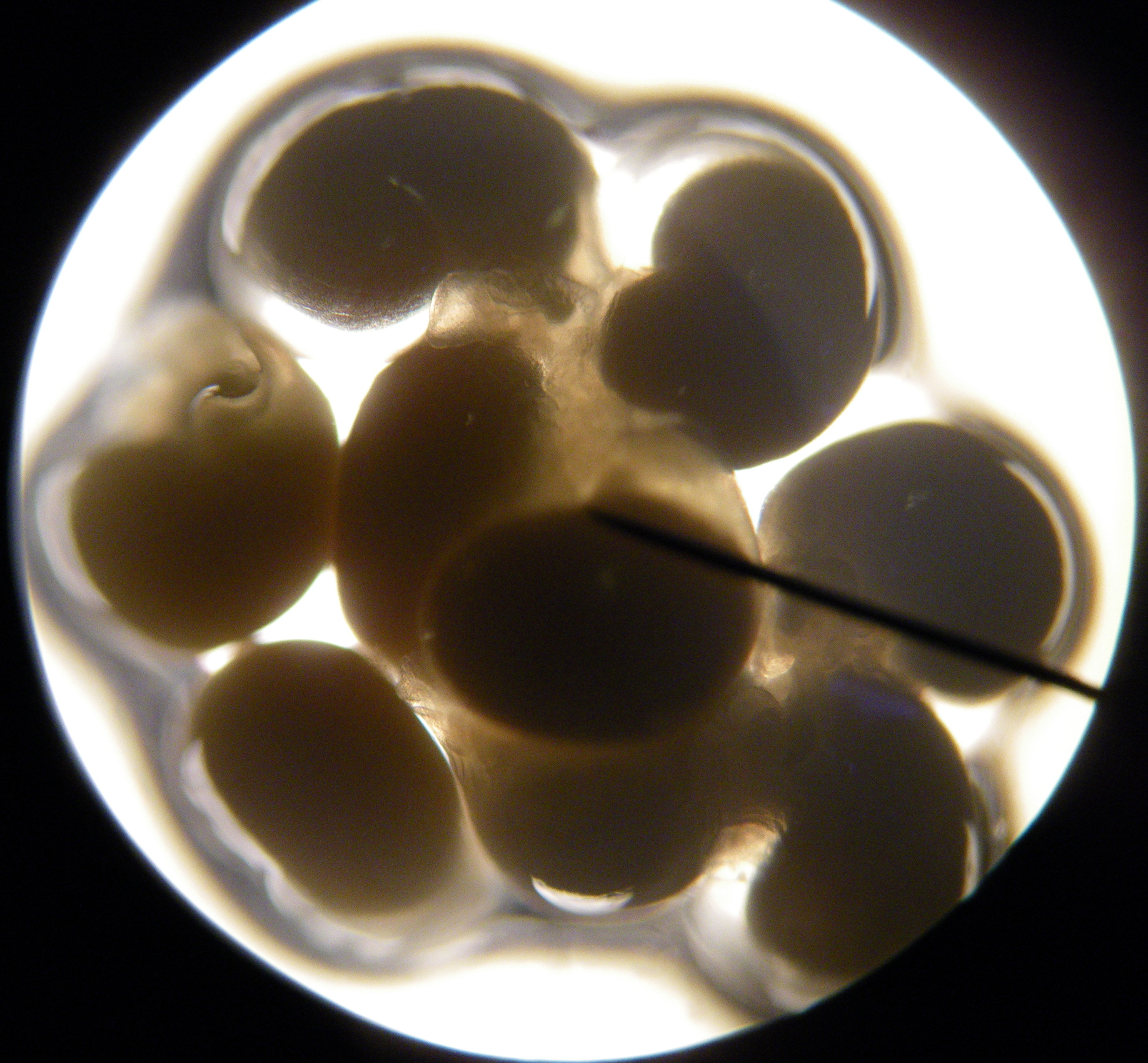

Channeled Whelk Babies under Microscope

Under a microscope at low magnification, you can detect individual shell development. The one furthest left clearly shows the developing siphon canal at the top.

Baby Channeled Whelk for Size Comparison

The casing pictured above came from a channeled whelk egg chain that the Turtle Journal team collected at Mayo Beach in Wellfleet Bay about four weeks ago. While still suspended in mucus-like fluid, the tiny whelks were further along in their development with more mature shell formation. All other casings in this string were empty and presumably tiny whelks had already emerged. We include this photograph to give you a better sense of the size of the babies as they begin to emerge as viewed between Don’s index finger (top) and thumb, and to contrast these baby whelks on the cusp of emergence with the ones from Burton Baker Beach that were still developing.

[…] Turtle Journal ” Blog Archive ” The Large and the Small of It (Whelks) […]

[…] shell exhibits a dextral aperture. For more information about these local northern whelks, see The Large and the Small of It (Whelks).  From Vanderbilt Beach in North Naples, Florida comes a more sinister snail. The lightning […]

Thank you sooo much for this info on whelks! I found a dehydrated egg casing today at the beach with my son. (We live on Cape Cod, MA) I had no idea what it was until I opened one of the pods. So cool! Although sad that these little ones didn’t make it out into the ocean.