Sunny November Lures Terrapin Hatchlings into Deathtrap

In the Great White North we’ve enjoyed a long string of beautiful November weather. This normally overcast month has been sparked by sunshine and temperatures poking into the upper fifties. Clear skies allow dunes to bake under the sun, and while humans and seals and other warm blooded-critters savor the unexpected warmth, these unusual conditions lure diamondback terrapin hatchlings to their death. Twelve babies would have died on Monday if not for the serendipitous intervention of the Turtle Journal team.

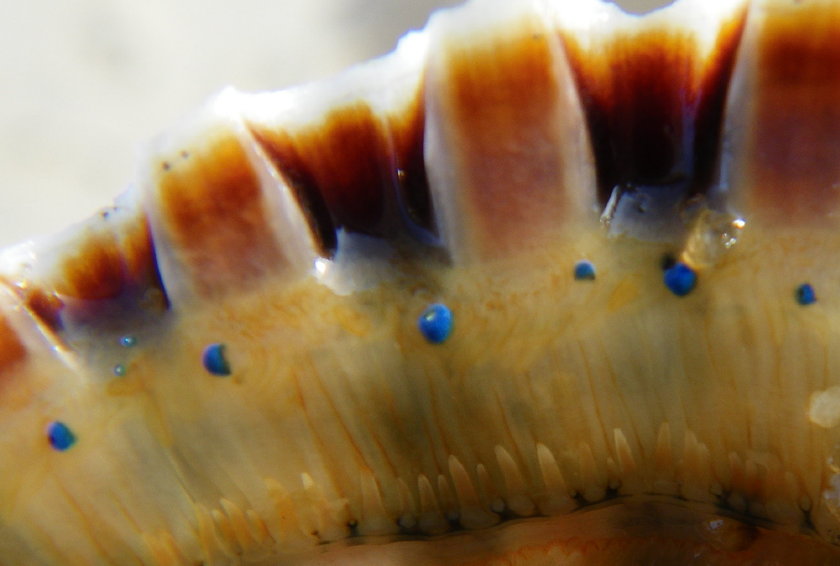

Cold-Stunned, Blinded Diamondback Terrapin Hatchling

Sunny November played a cruel trick on hatchlings over-wintering in late nests.  White sandy dunes absorbed days of sunshine, baking terrapin egg chambers buried several inches below ground.  Warm sand coaxed babies out of winter brumation, cuing these tiny hatchlings to tunnel for freedom.  In a normal overcast fall, without a long string of sunny November days, these hatched but unemerged babies would have slept in their nests until the first warm days of May. Cold-blooded turtles don’t “hibernate” like mammals, sleeping straight through the winter until springtime. Instead, these reptiles “brumate.” Although the two processes are similar, the difference can be critical if a bit subtle. Brumation is triggered by temperature alone and not by season of the year. A cold snap can drive turtles into summer brumation and a warm stretch in November or December can prompt reptiles to emerge from brumation … while hibernating mammals are snugly snoring away. For baby hatchlings, that tiny difference can be fatal … as it would have been on November 10th.

Confused Terrapin Hatchling Tracks

The Turtle Journal team had to split up on Monday. One half attended a board of trustees meeting, and the lucky half got to head into the field to adventure and to look for nature to happen. Pure serendipity brought Sue (the lucky half) to Sandy Neck in Barnstable for a stroll through the dunes along the salt marsh trail.  An early indication that something was surely amiss was finding hatchling tracks scattered across the dunes in confused patterns that seemed to circle and close on themselves. First, 10 November is NOT a day when one expects to see ANY terrapin tracks. But secondly, the confused patterns indicated that these hatchlings were in BIG trouble.

Click Here to View Video in HIgh Quality

Cold-Stunned Terrapin Hatchlings Wander Blindly in Circles

Scouting the tracks, Sue soon found her first cold-stunned hatchling, stumbling across the dune, eyes blinded by the cold, wandering in circles. Once these hatchlings had emerged from their warmed nests, the stinging reality of cold November winds nearly flash froze their dreams of scrambling to freedom in the marsh. Their body temperatures dropped, they entered a walking stupor, and they were cold to the touch. Their eyes were closed and their limbs stiff. They crawled aimlessly until some just froze in place.

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

Wobbly, Blinded, Cold-Stunned Hatchlings Near Death

In all, Sue rescued twelve cold-stunned and nearly dead hatchlings. Unfortunately, she was too late to save two others that had already succumbed to hypothermia. Luckily, we have had extensive experience dealing with cold-stunned sea turtles and have successfully applied those techniques to their non-migratory marine brethren. Once out of the debilitating wind, rescued babies began to breath more easily and to relax their frozen muscles. A few opened their eyes as they rested in secure container for the ride back to the lab at Turtle Journal Headquarters.

Click Here to View Video in High Quality

Cold-Stunned Hatchlings Recuperating in Warm Tank

We are always amazed at how resilient terrapins can be. Given a few hours of gradual, gentle warming and appropriate TLC, baby turtles that seemed within a whisper of death snapped back to playful liveliness. We understand only too well that these hatchlings may not be able to return to the wild until next spring. But their return to the salt marsh in May is a superior outcome to becoming crow bait in November.

Maze of Hatchling Tracks Leading Nowhere

One question we needed to assess was whether these cold-stunned hatchlings had newly emerged from a nest or had emerged sometime in the past, but decided to remain buried upland … as we have observed for some subset of hatchlings. Two key factors decided in favor of newly emerged nests. First, all the hatchling still sported an extremely sharp egg tooth, suggesting that they had recently pipped. Secondly, Sue back-tracked most of these hatchlings to emergence holes and nests.

Cold-Stunned Hatchling Collapses after Blind Wandering

November 10th sets a record for diamondback terrapin emergence within our research area. Yes, we have seen a single hatchling now and then in late fall, but never so many that clearly had emerged directly from their natal nest. The Turtle Journal team was lucky to be on hand to document the event and to save twelve hatchlings that had been tricked by a cruel November into a certain deathtrap.